The NHS COVID-19 app for England and Wales is one part of the toolkit for curbing the spread of COVID-19. But how effective is it in practice? Our Nature paper examines its impact in Autumn / Winter 2020.

First, some background. One of the key things to know about the spread of COVID-19 is that up to around half of all infections come from people who were not at the time experiencing any symptoms. To control the spread, then, requires more than simply requiring symptomatic people to self-isolate - that can take a good chunk out of the reproduction number R (the number of people you would expect the average infected person to infect) but it will never be enough to bring R down below 1, which is essential for epidemic control. This is particularly true for new variants with higher basic reproduction rates. A broader toolkit is needed.

Vaccines are magnificent. They reduce the potential for people to get infected when they’re exposed to the virus, AND they reduce the infectiousness of the few who do, and therefore they play a huge role in reducing R. They are by far the best control measure but they obviously take time to develop and distribute. In the meantime, blanket measures like mask wearing, social distancing and travel restrictions can all reduce R considerably but come with obvious disadvantages. Ideally, we would reduce our dependency on these restrictive blanket measures as far as possible, and focus on quarantining only those people who are infectious. That’s where testing and tracing can play a key role.

In March 2020 we showed that contact tracing would need to be fast if it were to make an appreciable difference to the epidemic, motivating the development of digital contact tracing apps. The theory makes it clear that such apps could really help to reduce R, with their impact increasing with the number of app users.

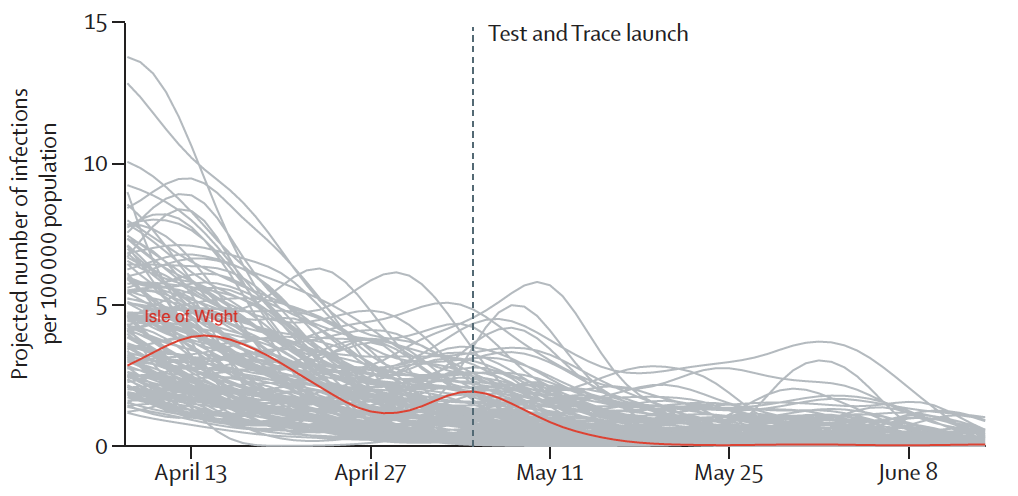

We were keen to see if the expected impact of the contact tracing function of the app was borne out in practice. In May 2020 there was an initial roll-out of the app on the Isle of Wight, an island to the South of mainland England. Our analysis pointed towards a favourable impact of the Test and Trace rollout there, but limited data meant it was hard to tease apart the specific impact of the app within the broader Test and Trace launch.

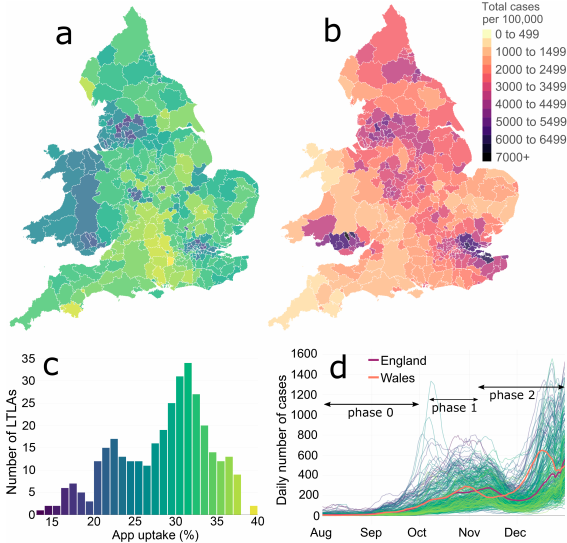

The app was launched for all of England and Wales on the 24th September 2020. There were many complications in assessing its impact against a background of frequently changing national and local restrictions, and distinguishing the effect of the app from other social and demographic factors. It’s certainly true that places with higher app uptake saw fewer cases, but it was challenging to determine how much of that is down to the app itself.

The app’s privacy-preserving design means that my co-authors (I only got involved quite late in the project) had very little data to work with. Nevertheless, they found a strong positive impact of the app. A modelling approach using the number of notifications sent out each day gave an estimate of 284,000 (108,000-450,000) cases averted in October - December, and a statistical approach using the geographical variation in uptake gave an estimate of 594,000 (317,000-914,000) cases averted. By comparison, there were 1.9 million cases actually recorded in that period. This shows that the Autumn wave could have been somewhere between 5% and 48% worse without the app. I appreciate that’s a very wide confidence interval, but that’s a natural part of doing science with real world data which is private by design.

The full peer-reviewed paper is here and well worth a read. I’ll just round up here with some take-home points:

The app works. I know it’s strange to think that something so apparently simple on your phone is having such an effect, but if you or one of your contacts gets exposed to the virus it can play a powerful role in breaking chains of transmission. For as long as there are infections around, please install it if you haven’t already, keep it active on your phone, and keep it updated. If it asks you to quarantine then yes it’s a pain to say the least, but I hope this study helps to assure you that your sacrifices are making a difference, and it really is reducing the chances of you inadvertently infecting people. Financial support may be available.

Contact tracing apps were developed rapidly all around the world last year. This study underlines the need to keep developing them for use wherever vaccines haven’t yet finished the job, and for use in the control of any future infectious disease outbreaks.